MAD matters

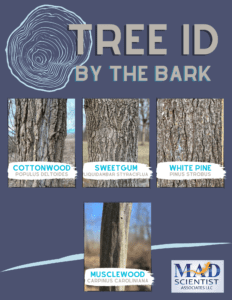

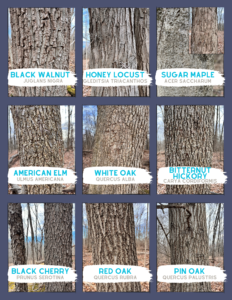

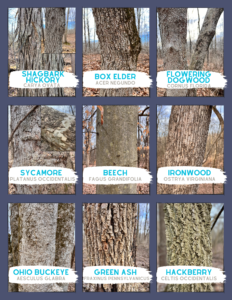

Tree ID- By the Bark

By: Jenny Adkins

February 17, 2023

Lower bark of a sycamore tree.

After a long stretch indoors recovering from elementary school viruses and planning and hosting our Women in Science event, Jenny was able to take some much needed time outdoors. Of course a botanist cannot just take a hike. They must focus on some botanical element to fuel themselves for the duration of the hike. In winter, your choices are limited to decrepit herbaceous stems and leaves, buds and twigs, fallen leaves, remnant fruit and husks, and trusty bark. She cataloged each tree species she came across by bark and came up with 22 species (not including shrubs and trees with trunks too small to get a decent photo, like pawpaw). Species and bark images are provided in the infographics below.

Learning to identify a tree by its bark seems easy enough, but there are species that look very similar, like some oaks and hickories, and some that look extremely variable, like sugar maples. Bark is a good place to start when determining a tree species, but backing up your ID with twig patterns, bud morphology, and other characteristics is a safer bet. Regarding bark, you can look deeper than what you see at first glance. Many species have additional clues that can help you deduce what species you’ve encountered. Take black walnut (Juglans nigra), if you peel back a piece of outer cambium (bark), you’ll notice a deep “chocolate” brown color. If you’ve found an american elm (Ulmus americana), you’ll notice the bark is spongy when squeezed, and when you pull some bark away, you’ll see what Jenny calls a “bologna sandwich” layering of pinkish-tan and brown bark. This distinguishes the american elm from a red elm (U. rubra), that and the habitat you’re in.

Under-bark of black walnut.

Under-bark of american elm.

Do you have any tricks or mnemonic devices that have served you well in the field? Do you have any questions about how to tell species apart? We’d love to hear from you!

If you’re in need of botanical assistance, contact Jenny Adkins. We’re always happy to take on tree surveys, floristic surveys, habitat mapping, invasive plant management, and restoration plantings. Let us know how we can help!

Bat Clearing Window Over for Ohio

By: Jenna Roller-Knapp

March 31, 2022

Image from Indiana DNR

Ohio is home to around ten species of bats. About half the population is tree-dwelling and solitary (migrating) while the other half are cave-dwelling and colonial (resident year-round). Of these species, four are state endangered, which includes the Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis), little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus), tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus) and northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis). The northern long-eared and Indiana bats are also federally threatened and endangered, respectively.

Species | Common Name | Ohio Resident/Migratory | Ohio State Status | Federal Status |

Eptesicus fuscus | Big Brown Bat | Resident | Species of Concern | – |

Lasionycteris noctivagans | Silver-haired Bat | Migratory | Species of Concern | – |

Lasiurus borealis | Red Bat | Migratory | Species of Concern | – |

Lasiurus cinereus | Hoary Bat | Migratory | Species of Concern | – |

Myotis leibii | Eastern Small-footed Bat | Resident | Species of Concern | – |

Myotis lucifugus | Little Brown Bat | Resident | Endangered | – |

Myotis septentrionalis | Northern Long-eared Bat | Resident | Endangered | Threatened |

Myotis sodalis | Indiana Bat | Resident | Endangered | Endangered |

Perimyotis subflavus | Tri-colored Bat | Resident | Endangered | – |

| Nycticeius humeralis | Evening Bat | Migratory | Special Interest | – |

The reason so many listed bats because there has been an estimated 90% decline in the group’s populations, largely due to white nose (Pseudogymnoascus destructans; WNS) syndrome. WNS arrived in the northeastern US from Europe in 2006 and has since spread across the country, even documented now in Washington and in Canada. Because bat species in North America haven’t evolved with the fungus, it’s having much more devastating impacts compared to European populations. WNS is also found to affect hibernating bats more than migrating species as it spreads rapidly in the cool environs of a cave and the animals are often densely packed making it easy for transmission to occur.

Although there doesn’t seem to be a solution to stop WNS at this point, in order to help the populations, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) are working to protect the species’ summer roosting habitat and hibernacula. They have blocked entrances to many caves and mine entrances to reduce human spread of WNS and encourage people to not disturb sensitive rock ledges. There are also many efforts to protect water resources and remove invasive species so that bats can have access to these critical foraging areas.

These organizations have also instated seasonal tree clearing recommendations if trees need to be cleared for development or other land impacts. For Ohio, the clearing window is between Oct. 1 and March 31 or Nov. 15 and March 15 if project is near a fall swarming site and/or known hibernaculum. ODNR and USFWS also check records of where T&E bats have been documented to see if a project area is within a 2.5 to 5 miles radius from known locations of bat occurrence. If a project has a federal nexus (permit or funding), no clearing should occur even within the clearing window before there is consultation with USFWS.

Images sourced from Maryland Biodiversity Project & Indiana DNR.

World Water Day- A History and Celebration

By: Dan Hribar

March 21, 2022

To bring greater attention to the global need for sustainable sources of freshwater and sanitation for all people, member states of the United Nations have begun celebrating World Water Day. This is an annual event established on March 22, 1993. Observation the day of is just one component of a yearly information and events campaign that focuses on a distinct theme and typically includes multiple summits, meetings, and proceedings. For 2022, the selected theme is groundwater resources, which are the primary source of water for drinking and agricultural irrigation in many countries. This year’s celebration of World Water Day also marks the 4th in the International Water Action Decade, which was declared by the United Nations General Assembly in 2018 to accelerate efforts to address water-related challenges.

Despite considerable progress on many fronts, it is estimated that 2.1 billion people still do not have access to clean drinking water, while more than double that number lack safely managed sanitation services (WHO/UNICEF 2017). Although these issues are less pronounced here in the United States—97.3% of population using safe drinking water (SDG Tracker, 2018)—preservation and improvement of clean water access has never been more important in our country. Prior to the passage of the Clean Water Act (1972), Safe Drinking Water Act (1974), and other key reforms that reshaped the U.S. water landscape, major contributing sources of water pollution and overexploitation resulted in waterways so mistreated that they became flammable (in extreme cases) and were frequently declared unsuitable for drinking or recreation. Even now, recent and ongoing issues such as the Flint water crisis, western megadrought, and growing intensity of natural disasters highlight the fragile nature of our freshwater sources.

Thanks in large part to the passage of water legislation and greater enforcement of pollution regulations, many major waterbodies that provide drinking water to tens of millions of Americans are on the road to recovery. A grand indicator of this progress came in 2019, when state officials declared fish from Ohio’s Cuyahoga River safe to consume almost five decades to the day after the river’s infamous fire that helped spur the environmental movement. Ecological restoration and protection of freshwater resources continues to gain traction across much of the country, as engaged citizens, businesses, non-profits, and government entities alike seek to promote a new paradigm in managing water for both people and planet.

It’s been said that water is what we all have in common (among other things). At MAD, we celebrate our water resources because they are an integral part of what we do. As World Water Day approaches, we hope that you will consider what clean water means to you as well and take some time to enjoy our blue planet!

Invasive Species Awareness Week- Reed Canarygrass

By: Cody Wright

March 3, 2022

One NNIS that doesn’t get quite enough attention is Reed Canary Grass (Phalaris arundinacea). Beginning in the 1800s, this grass has been widely used as livestock forage, for erosion control, and in landscaping. Reed Canary Grass (RCG) prefers moist, poorly-drained soils but can be found thriving in various types of habitats. From standing water to dry upland areas, this plant is highly adaptable. This adaptability, along with the production of easily dispersed seed and dense biomass via rhizomes, is what gives this plant it’s invasive nature.

While it has been determined that there is a native genotype of Phalaris arundinacea, it is not possible to distinguish this difference without genetic analysis. In a field-setting, then, this simply cannot be done, and it is commonly assumed based on the density that the species is more problematic than would be expected of a typical native genotype.

Management of RCG can be performed by smothering, or solarization, for at least one growing season by covering the plants with a layer of black plastic. This method is a useful, chemical-free alternative. An integrated method of both mechanical and chemical means of control is also very useful when dealing with this grass. Mowing down RCG in the early fall to force it to tap into its energy reserves followed by a strategic herbicide application to regrowth has been proven effective in efforts to control this species.

In January of 2018, the Ohio Department of Agriculture (ODA) introduced a list of 38 invasive plant species that are to be banned for sale, distribution, and propagation in the state of Ohio. Although RCG was not originally included in the list, the Ohio Invasive Plants Council (OIPC) submitted a proposed addition to the list consisting of 29 more species in September of 2018, this time including RCG. In December of 2021, ODA confirmed that they plan to add 26 of the 29 additional invasive plants to their list, which will now include RCG. Although this ban does not include Phalaris arundinacea plants or seeds intended for animal feed, this is a major step in aiding in the management of invasive species.

Like other NNIS, there are plenty of native substitutes for the variable habitat types where this invader can be found. Swamp Rose (Rosa palustris) , Obedient Plant (Physostegia virginiana) , Ohio Spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis), Sneezeweed (Helenium autumnale), New England Aster (Aster novae-angliae), Monkey Flower (Mimulus ringens), Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) , Rice Cutgrass (Leersia oryzoides), Prairie Cordgrass (Spartina pectinata), and Soft Rush (Juncus effusus) all make great, showy replacements.

Floodplain smothered by Phalaris.

Planting native trees and shrubs in hopes to create shade to weaken Phalaris.

Clearing space in Phalaris thatch to plant trees into.

Invasive Species Awareness Week- Cattail

By: Cody Wright

March 2, 2022

Broadleaf Cattail inflorescence on left, Narrow-Leaf Cattail on right.

In Ohio, our native Cattail, Typha latifolia, is being pushed out of its niche by its invasive cousin, T. angustifolia. These two species can interbreed and produce viable hybrid offspring, T. x glauca, which also exhibit invasive tendencies. It is thought that T. angustifolia was first introduced to the U.S. along the Atlantic seaboard via the dry ballast of European ships coming into harbor.

The key characteristic that can be used to identify between these species is the gap, or lack thereof, between the male and female flower. Yes, that portion of the plant that humorously resembles a corndog is actually the flower spike that the plants use for sexual reproduction. The native cattail has no gap between the large, brown female flower and the male flower, whereas the invasive and hybrid cattails have a 1 to 4 inch gap between their flowering bodies. These seed heads create thousands of tiny, wind-dispersed seeds. Along with sexual reproduction, cattails are able to reproduce vegetatively through rhizomes that form thick mats and dense stands. All cattails can create these near impenetrable colonies , and it is even suspected that cattails have allelopathic properties, similar to those of the invasive Bush Honeysuckles. For the sake of biodiversity, management efforts should be taken to control overabundant cattails, especially the invasive species.

Mechanical thinning (or complete removal of the invasives) in “deep” water situations can be very helpful. By cutting the stalks beneath the water level the plant’s ability to exchange gasses is compromised, essentially suffocating it. For shallow water or saturated soil settings, meanwhile, herbicide application may be the best option. For a thick monoculture, broadcast foliar spraying of an aquatic-approved herbicide and non-ionic surfactant is suitable. For smaller infestations, hand-wicking of the herbicide is advisable to decrease non-target environmental impacts. One biological control method that is also known to be effective is the support of a stable muskrat population where appropriate. Muskrats graze on the shoots of the cattail, performing selective thinning. No matter which management option you choose, it is likely to take multiple years of treatment to achieve complete eradication.

…we’ll continue tomorrow with the tale of Reed Canarygrass.

Invasive Species Awareness Week- Callery Pear

By: Cody Wright

March 1, 2022

Photo Credit: Ohio Environmental Council

This iconic suburban tree has come to be known by many different trade names throughout the years: Bradford Pear, Cleveland Select, Metropolitan Pear. Yet they all derive from one species native to China—the Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana). This NNIS was introduced to the U.S. in the mid-1900s as an ornamental street and yard tree and quickly gained popularity for its bright white, early spring blooms and colorful fall foliage. Through selective cultivation, multiple sterile cultivar types were created and mass produced for public purchase. According to Dr. Theresa Culley, Professor and Head of the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Cincinnati, “It is not the cultivar itself that is invasive, per se, but rather the problem arises when two different cultivars cross-pollinate.” Dr. Culley has an ongoing research project at UC using DNA examination and tracking of the various cultivar crosses and invasive trends. More on Dr. Culley’s research can be found at www.culleylab.com.

The premise behind these sterile cultivars is that when a cultivar is pollinated by another individual of the same cultivar, Cleveland Select x Cleveland Select, for example, the cross is unsuccessful in producing viable seed since the two were genetically the same. However, since multiple types of cultivars were created and grafted, it is possible for the different cultivars to cross-pollinate with each other because they are of the same species but genetically different. Importantly, this cross-pollination has led to an abundance of viable seed production and has allowed the Callery Pear to gain a foothold across much of the eastern United States.

Photo Credit: Ohio Environmental Council

Although Pyrus calleryana is a pear tree, it does not bear the large, juicy fruit that one would typically expect from such a plant. Instead, it produces thousands of small, hard, grape-sized fruits . While unpalatable to humans, these berries are the perfect snack for a hungry songbird. Does this dispersal tactic sound familiar to you?

This mass production of seed is the driving force behind the Callery Pear invasion. Since escaping cultivation, this tree has established itself across many habitats and disturbed areas, most notably lining highway corridors and old fields throughout the state. Next time you are out for a sunny spring drive, be on the lookout for a wall of white , and know that it is more than likely this nasty invader.

Luckily, there is hope for dealing with this nuisance tree. Pyrus calleryana will officially be banned for nursery sale in the state of Ohio on January 7th, 2023. This measure alone will help combat the spread to a small degree, but further intervention is crucial to successfully eliminating Callery Pear from the native landscape. Our trained staff at MAD utilize integrated pest management techniques to complete projects dealing with Callery Pear, and the results can be astonishing . Like many other invasive plants, herbicides are effective when used in combination with mechanical methods and has proven itself time and time again.

When looking to replace this tree with a native species, Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida), Black Tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica), and Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.) are all great candidates! Just remember to research the desired species’ needs and responsibly source your new natives.

Felled Callery Pear in foreground. Remaining pear to be cut in background.

…we’ll continue tomorrow with the tale of Narrow-leaved and Hybrid Cattail.

Invasive Species Awareness Week- Callery Pear

By: Cody Wright

March 1, 2022

Photo Credit: Ohio Environmental Council

This iconic suburban tree has come to be known by many different trade names throughout the years: Bradford Pear, Cleveland Select, Metropolitan Pear. Yet they all derive from one species native to China—the Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana). This NNIS was introduced to the U.S. in the mid-1900s as an ornamental street and yard tree and quickly gained popularity for its bright white, early spring blooms and colorful fall foliage. Through selective cultivation, multiple sterile cultivar types were created and mass produced for public purchase. According to Dr. Theresa Culley, Professor and Head of the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Cincinnati, “It is not the cultivar itself that is invasive, per se, but rather the problem arises when two different cultivars cross-pollinate.” Dr. Culley has an ongoing research project at UC using DNA examination and tracking of the various cultivar crosses and invasive trends. More on Dr. Culley’s research can be found at www.culleylab.com.

The premise behind these sterile cultivars is that when a cultivar is pollinated by another individual of the same cultivar, Cleveland Select x Cleveland Select, for example, the cross is unsuccessful in producing viable seed since the two were genetically the same. However, since multiple types of cultivars were created and grafted, it is possible for the different cultivars to cross-pollinate with each other because they are of the same species but genetically different. Importantly, this cross-pollination has led to an abundance of viable seed production and has allowed the Callery Pear to gain a foothold across much of the eastern United States.

Photo Credit: Ohio Environmental Council

Although Pyrus calleryana is a pear tree, it does not bear the large, juicy fruit that one would typically expect from such a plant. Instead, it produces thousands of small, hard, grape-sized fruits . While unpalatable to humans, these berries are the perfect snack for a hungry songbird. Does this dispersal tactic sound familiar to you?

This mass production of seed is the driving force behind the Callery Pear invasion. Since escaping cultivation, this tree has established itself across many habitats and disturbed areas, most notably lining highway corridors and old fields throughout the state. Next time you are out for a sunny spring drive, be on the lookout for a wall of white , and know that it is more than likely this nasty invader.

Luckily, there is hope for dealing with this nuisance tree. Pyrus calleryana will officially be banned for nursery sale in the state of Ohio on January 7th, 2023. This measure alone will help combat the spread to a small degree, but further intervention is crucial to successfully eliminating Callery Pear from the native landscape. Our trained staff at MAD utilize integrated pest management techniques to complete projects dealing with Callery Pear, and the results can be astonishing . Like many other invasive plants, herbicides are effective when used in combination with mechanical methods and has proven itself time and time again.

When looking to replace this tree with a native species, Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida), Black Tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica), and Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.) are all great candidates! Just remember to research the desired species’ needs and responsibly source your new natives.

Felled Callery Pear in foreground. Remaining pear to be cut in background.

…we’ll continue tomorrow with the tale of Narrow-leaved and Hybrid Cattail.

Invasive Species Awareness Week- Bush Honeysuckle

By: Cody Wright

February 28, 2022

If you ask any conservation professional or land manager to name the greatest challenge they face, among the most common responses you will get is the never-ending effort to slow non-native and invasive species (NNIS). Ohio has become home to numerous such plant species that wreak havoc on the local habitats and ecosystems in which they take up residence. Four of the most notorious and problematic NNIS are the Bush Honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.), Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana), Narrow-leaved and Hybrid Cattail (Typha angustifolia, T. x glauca), and Reed Canary Grass (Phalaris arundinacea). Let’s take a closer look at why each of these species present a concern and what is being done to help prevent their continued spread.

Bush honeysuckle species were first introduced to the U.S. in the late 1800s, these highly adaptable shrubs were previously coveted by the horticulture industry for use as an ornamental landscape plant due to their attractive white to pink flowers and plump, red-orange berries . They are fast-growing and shade-tolerant with bright green foliage that persists from early Spring into late Autumn. Once mature, bush honeysuckles produce copious amounts of seed, which are encased by fleshy fruits that are readily consumed by songbirds and other wildlife, thereby dispersing them widely across the local ecosystem. There is an extensive body of research surrounding the impacts of honeysuckle, with many studies suggesting that bush honeysuckles exhibit allelopathic tendencies (e.g. Cippolini, Stevenson, & Cippolini, 2008) and reduce nutrient deposition in the underlying soil (e.g. McEwan, Arthur, & Alverson, 2012), among other things. Such characteristics have given these shrubs a competitive edge, providing them the capacity to quickly overrun the understory of woodlands, right-of-ways, and roadsides. This invasion is rapidly displacing native flora and providing relatively little benefit to wildlife. Although the flowers and berries provide a source of food for pollinators and birds in their respective seasons, these food sources are to wildlife what a bag of potato chips and a candy bar are to us: junk food!

To protect the health of the ecosystem, removal and replacement of these plants is paramount. Although smaller, individual

Honeysuckle wouldn’t be so successful if not for its stubborn persistence, however. Consequently, multiple treatments may be necessary in many areas to reduce

Lonicera maackii in bloom (Native Plant Trust)

Lonicera morrowii in bloom (Native Plant Trust)

Lonicera tatarica in bloom (Native Plant Trust)

…we’ll continue tomorrow with the tale of Callery Pear.

Floristic Quality Assessments

By: Jenny Adkins

May 12, 2021

This year, we were thrilled to have the opportunity to work with Great Parks of Hamilton County, conducting a Floristic Quality Assessment (FQA) for several of their conservation and public parcels. This year marks the 6th field season that we’ve completed these surveys for Great Parks. We’ve covered a lot of ground in the Cincinnati area, and it’s always been an adventure.

This year, Jenny and Logan teamed up to survey the predesignated plots. It was an especially wild sampling run with rain, sun, snow (and all of the associated temperature fluctuations), long hikes, flooded boots, Lonestar and dog ticks, poison ivy, nettles, but all of that was worth it for the new plant finds, wildflowers, breathtaking forest views, and wildlife.

For those unfamiliar with the botanical world and associated surveys, the FQA is a quantitative survey that measures plant diversity and quality within a unique habitat to determine how intact (disturbance free) it is in comparison to reference communities throughout the state. It was developed by the Ohio EPA’s Division of Surface Water and Wetland Ecology Group in 2004. Basically, every native plant known to occur in Ohio was given a Coefficient of Conservatism (C of C), ranging from 0-10, that indicates how specific a plant is in the habitat it will grow. For example, your common evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) has a C of C of 1, indicating it is a highly tolerant species capable of growing (naturally) in many habitats under a variety of conditions. In contrast, sycamores (Platanus occidentalis) the iconic white-trunked trees growing along stream and riverbanks have a C of C of 7, indicating it is much more specific in the habitat you will naturally find it growing. While it is adaptable, it primarily grows along moving water systems and associated floodplains with moist, well-drained soil. Some plants are so finicky that you’ll only find them on north-facing forested slopes, or on certain plants’ roots, or limestone barrens.

So far, our team has recorded over 230 plant species- all mostly floodplain species growing near the Miami Whitewater River or tributaries. Since 2013, the first year we surveyed, we’ve logged around 800 plant species within the 1,300 or so plots. Its certainly a labor of love and we never tire of plants- though by dusk we’re certainly ready for a warm, non-granola meal!

We hope you’ll enjoy these photos of our FQA adventures in Hamilton County, Ohio.

Spring Beauties

By: Jenny Adkins

April 12, 2021

Today, we highlight the dainty and captivating Spring Beauty (Claytonia virginica).

This common wildflower is one of the first to bloom in the spring, bringing a cheerful presence to the forest floor. It blooms throughout the spring, opening towards the sky on sunny days and closing to a nod on dreary days. Native bees, flies, ants, and Lepidoptera frequent Spring Beauty as a source of pollen and nectar.

It grows throughout central and eastern North American dry-mesic woodlands where it thrives on nutrients from leaflitter and can complete its life cycle before trees leaf out and prohibit sunlight from reaching the forest floor. It spreads by seed and corm, which are hard, bulb-like storage reserves that sprout new stems.

Interestingly, we looked into the variation in petal color (dark pink to light pink, to white) and found a great post from the In Defense of Plants blog, summarizing the work of Dr. Frank Frey at Colgate University. Essentially, the white variants are passed over by herbivores (good), but less frequently visited by pollinators (bad). On one hand, you’re not eaten and have another year to attempt seed production. On the other, you’re not putting your all into a good seed yield this year and your chance of reproductive success is low. The variants with more pink coloration (pigment compound cyanidin) are more attractive to pollinators and generally produce more viable seed. Amazingly, if there are neighboring populations of white flowered plants, the Spring Beauty is more likely to be pink due to competition for pollinators. Fascinating, right?!

Let’s Talk Lesser Celandine

By: Jenny Adkins

April 8, 2021

Yes, it’s beautiful. It’s one of the first things to come up in spring along floodplains and mesic soils, carpeting the ground in lush green foliage and cheery yellow flowers. You’ll notice at second glance that beneath that lush carpet, there’s NOTHING else growing under or around it. These areas should be loaded with diverse wildflowers- harbinger of spring, bluebells, anemone, phlox, ginger, bloodroot, solomon’s seal, ramps, trout lilies, spring beauty, Dutchman’s breeches, geranium, orchids, twin leaf, trilliums, toothwort, cresses, violets, mayapple, larkspur, hyacinth…just to name a few fan favorites.

Yes, you’ll see pollinators on the flowers. This does not make up for the array of plant species our native insects have coevolved with. One plant does not a balanced diet make. There’s also research showing a reduction in seed set for native ephemerals because pollinators are transferring celandine pollen to them (Masters and Emery, 2015).

There’s much to learn regarding the treatment of celandine and the recovery of once infested areas. Anecdotally, we’ve observed other non-native species and adventive natives trying to muscle out one another near or within areas where celandine is prevalent. We’ve also observed that when an area is cleared of one invasive, another (often a vine) delights in the open space and begins to creep and climb over unoccupied area. Therefore, one must be vigilant of opportunists and other invaders when creating a management plan.

Unfortunately, there’s not much to do aside from herbicide. We currently have crews finishing up foliar applications of systemic herbicide to highly infested areas. There’s a narrow window in which to treat before it’s in full bloom and still able to produce seed. Dense infestations may require more than one treatment because lower leaves aren’t adequately covered and thus don’t effectively transport the herbicide to the root system.

You can voice your concern to land managers and do your part on private land to reduce the spread of this highly aggressive plant.

Do enjoy the pollinators though!

Salamander Run

By: Jenna Odegard

March 1, 2021

The adult salamanders are present in pools for a short time, often just one to two weeks. The males deposit spermatophores (up to 80 per male) on leaves and sticks underwater. They lead females to the area in hopes that they will accept this donation and use it to fertilize their eggs. Females release an average of 200 eggs within a thick, firm, jelly-like mass, which is often attached to woody debris in the water in secretive locations. Some salamander species will stay nearby and guard the eggs from predators, however others, such as spotted salamanders, make no further investment of parental care. Males typically stay longer in the pool, likely to increase their chance of fertilizing more eggs. The egg mass provides moisture needed to survive as water levels fluctuate. The eggs masses are distinguishable by species based on shape, deposition location, and amount of eggs per mass.

Salamanders return underground by way of abandoned burrows of small mammals or crayfish, however the eastern tiger salamander is a proficient digger and can make its own tunnels. These tunnels vary between 1-1.5 meters in depth. Here they spend the majority of their lives, consuming invertebrates and are kept safe from freezing temperatures in winter. They do not eat during the winter, but rely on their fat storages. They will not eat again until after they have bred. In vernal pools, they eat small critters including zooplankton, fairy shrimp, spiders and worms, mosquito larvae and flies. Sometimes, especially when the pool is drying up or in times of overcrowding, they may eat other salamanders! In turn, salamander eggs are often preyed upon by adult newts, wood frog tadpoles, crayfish, and some species of caddisfly. Adult salamanders are preyed upon by birds and snakes.

The eggs that successfully develop in the vernal pool metamorphose into small larvae. The length this that process is determined by the amount of water in the pool. They will develop visible feathery gills at the base of their head, and when they become adults, they lose these gills and transition to breathing by lungs, gain eyelids and a tongue. Tiger salamanders develop more slowly and often need water present through about August, but their metamorphosis, like other salamanders, can speed up if they sense the water is drawing down.

We hope you enjoy these amphibian harbingers of spring as much as we do!

Landscape Design and Ecological Restoration

By: Jonathan Stechshulte

February 18, 2021

The purpose of ecological restora

Enter ecological restoration, again. It could be argued that ecological restoration is a design profession that is not formally categorized as a design profession. But formalities aside, great ecological design requires an incredible amount of coordination and knowledge specific to the ecology that is being restored. Its implementation and success rides on more than just the creation of a “natural” appearance. Restoration ecology outcomes increase biodiversity, promote the conservation of at-risk systems, and restore historical ecologies from the ground up. These outcomes are quantifiable through ecological monitoring and assessment.

Bringing landscape architecture into the realm of ecological restoration is a natural combination of two fields. While restoration ecologists deal much less with the anthropogenic built environment, there is still a large amount of overlap in design and construction processes. Bringing landscape architecture into the field of ecological restoration allows a team to establish a well-rounded technical, scientific, and aesthetic suite of services for each project, as ultimately, the most successful ecological solutions are the ones that promote environmental synergy, interdisciplinary dialogue, and mutual understanding.

Restored Habitats – Built to Last!

By: Alexys Nolan

November 9, 2020

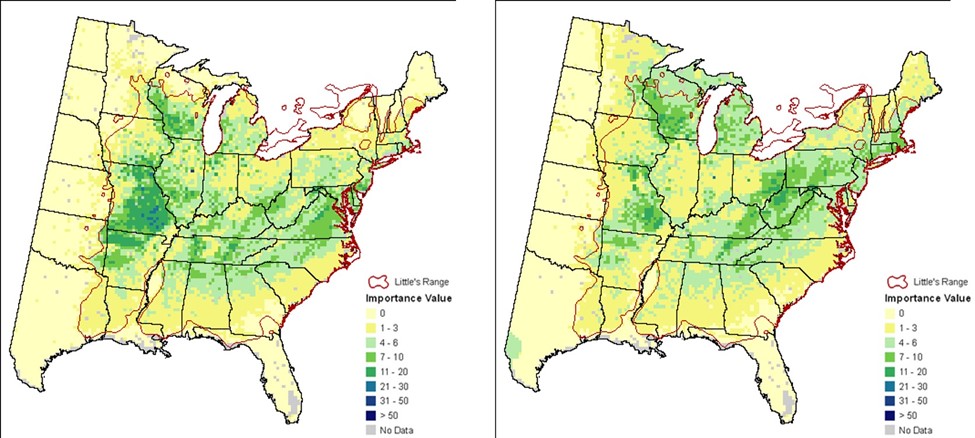

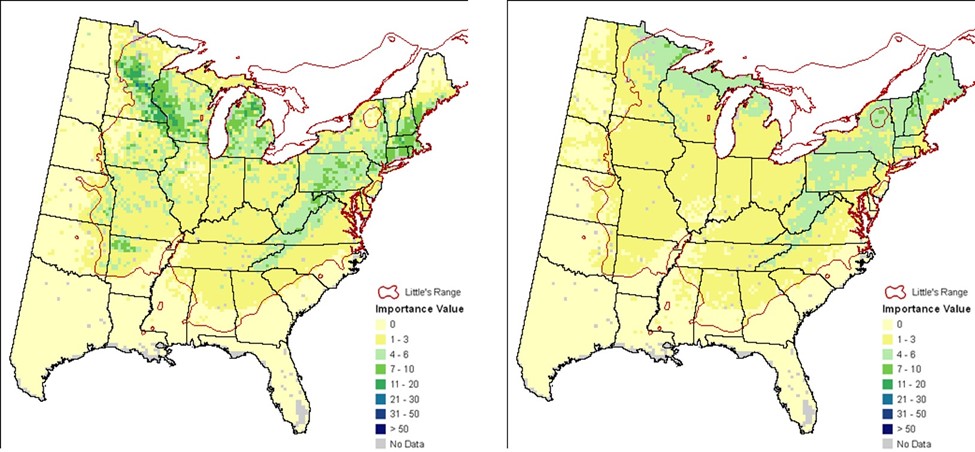

As weather patterns shift, so do suitable habitats for different plant species. Fluctuating temperatures, precipitation, and increases or decreases in flooding can all determine whether or not specific plants will be able to grow at a given site tomorrow, 20 years from now, and 100 years into the future. Luckily, these environmental changes can be scientifically predicted – helping us build a restoration plan that will stand the test of time!

Below are a few examples of climate change modeling from the U.S. Forest Service’s online atlas – a useful planning tool that you can check out here! http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/atlas.

References:

Prasad, AM; Iverson, LR; Peters, MP; Matthews, SN. 2014. Climate change tree atlas. Northern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Delaware, OH. http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/atlas.